Doubleday Double Talk Remembers is designed to connect fans with the game of baseball’s past one player and story at a time. A Doubleday Double Talk Remembers will be published every Friday and will go over the life and legacy of the players from our past, from Babe Ruth to Hank Aaron to Steve Dalkowski to Eddie Gaedel, every player has a story and Daryll Dorman and Giuseppe Vitulli are here to provide you with just that. Sometimes we forget about how important baseball’s past is, so Doubleday Double Talk Remembers is simply the writers at Doubleday Double Talk’s way to pay homage to the past of the beautiful game of baseball.

“A man has to have goals – for a day, for a lifetime – and that was mine, to have people say, ‘There goes Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived.’”

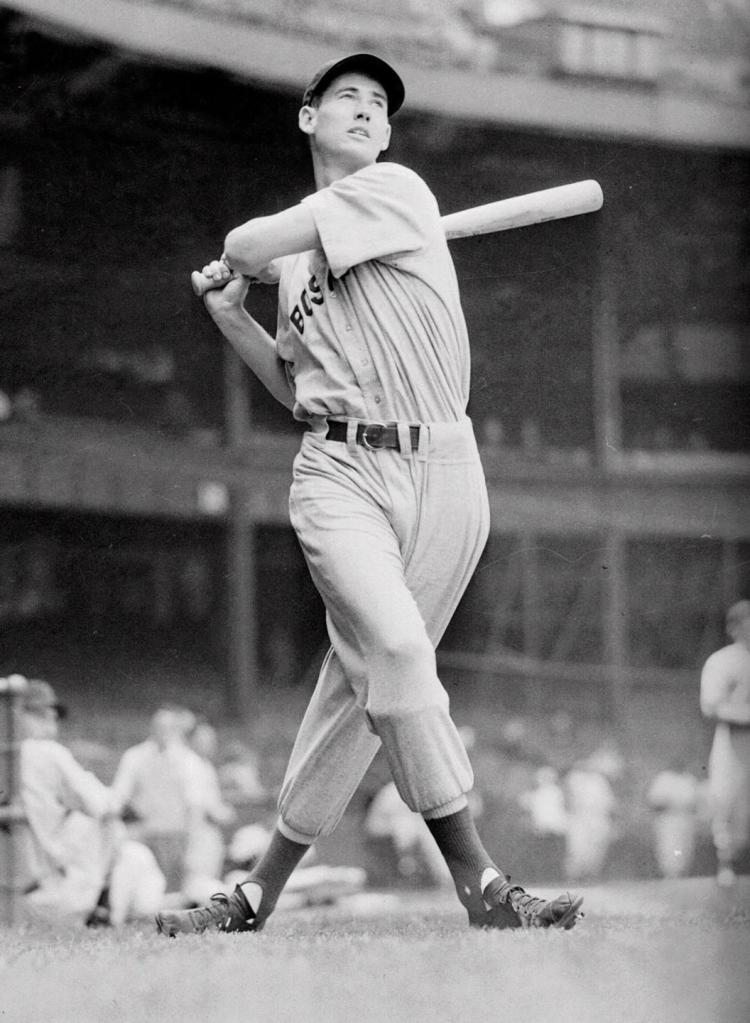

Theodore Samuel Williams was born on August 30, 1918, in San Diego, California and went from a poor kid in a dysfunctional family to the greatest hitter in the history of Major League Baseball.

At the age of 8-years-old, Williams was introduced to baseball by his uncle and former semi-professional pitcher, Saul Venzor, who had actually pitched against the likes of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in an exhibition game.

Williams’ love of baseball never died as he was constantly hitting at his local sandlot where no player could match his undeniably incredible hitting ability.

Ted Williams grew up in the absence of his father Samuel Stuart Williams who worked first as a photographer and later as a U.S. Marshal, and his mother, May Venzor Williams who was an evangelist and a lifelong soldier in the Salvation Army. With his father regularly gone at work and his mother gone saving souls. Some nights, Ted and his brother Danny Williams were forced to sit outside until 10 o’clock at night for their parents came home to let them in the house. Ted Williams grew up resenting his parents and turned to baseball.

Ted played pitcher and was the star player on his high school team at Herbert Hoover High School (Fun Fact: My co-writer Daryll Dorman has actually played adult league baseball games at Hoover High School), hitting .538 in his Junior year while pitching his way to a stellar 16-3 record. The tall and scrawny Ted Williams also played American Legion Baseball where he would later be named the 1960 American Legion Baseball Graduate of the Year. Williams received offers from the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees while he was still in high school, but his mother decided that he was too young to leave home and Williams signed with a local Minor League club, the San Diego Padres.

Williams posted a .271 batting average on 107 at-bats in 42 games for the Padres in 1936 while unknowingly catching the attention of Boston Red Sox scout, Eddie Collins. Collins was originally scouting future Hall of Famer Bobby Doerr, but would later say, “It wasn’t hard to find Ted Williams. He stood out like a brown cow in a field of white cows.”

Ted Williams became a starter for the Padres in 1937 and hit .291 with 23 home runs while leading San Diego to a Pacific Coast League Championship. In December 1937, during the Winter Meetings, a deal was made between Padres’ General Manager Bill Lane and Collins, sending Williams to the Boston Red Sox and giving Lane $35,000, Dom D’Allessandro, Al Niemiec, and two other Minor Leaguers (quite the steal if you ask me). Williams received an invite to the Boston Red Sox’ 1938 Spring Training, to which he showed up 10 days late and was greeted by Red Sox equipment Manager who famously stated, “The Kid has arrived,” and the nickname “The Kid” was born.

Williams was sent down to the Double-A Minneapolis Millers where he hit an impressive .366 with 46 home runs and 142 RBIs. “The Kid” received the American Association’s Triple Crown and finished second in the voting for Most Valuable Player Award.

Williams would get an invite to Spring Training in 1939 and would be given William’s famous No. 9. Ted made the team and proceeded to have one of the greatest rookie seasons in Major League history in which he hit a stunning .327/.436/.609 batting line with 31 home runs, 145 RBI, 44 doubles, 11 triples, 131 runs. Williams became the first rookie to ever lead the league in runs batted in and set a rookie record for walks in a season with 107 (a record that would stand until Aaron Judge in 2017). Williams finished 4th in the American League MVP Award voting and although there was not a Rookie of the Year award yet in 1939, Babe Ruth declared Williams the Rookie of the Year, which Williams later said was “good enough for me”.

The Boston Red Sox were so impressed with Williams’ rookies season that they added a new bullpen in right field to bring the right field fence in 20 feet. This addition was commonly nicknamed “Williamsburg” due to the fact that the addition was clearly for Williams. Williams’ sophomore season was almost as impressive as his rookie season, and despite a decline in power (even with “Williamsburg”), Williams hit an amazing .344 with 23 home runs and 113 runs batted in. While everyone knew Williams was a special talent, nothing could prepare anyone for what Williams was about to do in the 1941 season.

“If I had known hitting .400 was going to be such a big deal, I would have done it again.”

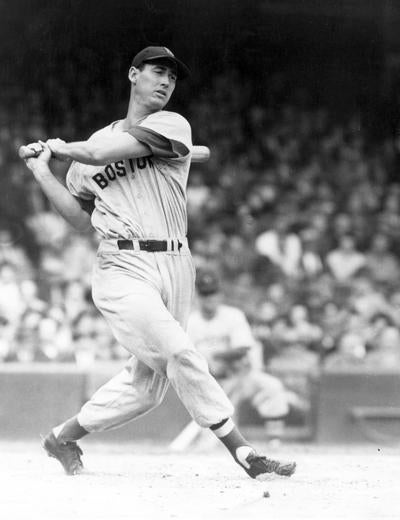

In the same year that Joe Dimaggio would break the Major League Baseball’s consecutive games with a hit record with 56 games in a row with a hit (we will get to Joltin Joe Dimaggio later), Ted Williams would also do something that baseball fans would remember for the rest of sports history, hit .400.

1941 was an incredible year for Williams in which he hit 37 home runs and batted in 120 runs, missing the Triple Crown by 5 runs batted in. Despite this, the real story was Williams batting average. Through August, Williams was hitting .402 and Williams said that “just about everybody was rooting for me” to hit .400 in the season. Williams continued to rake and by mid-September, Williams was hitting .413. Williams then suffered a horrible slump and by the final day of the season, Williams was hitting .39955, which would have been rounded up to an even .400. Williams’ manager offered to bench Williams from the doubleheader to guarantee him the legendary .400. Williams’ refused.

“If I’m going to be a .400 hitter,” he said at the time, “I want more than my toenails on the line.”

What would later take place was the stuff of legends. In a meaningless doubleheader to end a mediocre season against a last-place team, Williams decided to play and would go on to go 6-8, bringing his season batting average from .39955 to a stunning .40570 or after rounding, an even more impressive .406. Ted Williams had hit .400 and he had done it the honest way with no excuses. “There was not a questionable hit among the group,” wrote the Inquirer. “All were slashing drives that whistled through the infield or fell far out of reach of the outfielders.”

To this day, no man has hit .400 since Williams with the closest being Tony Gwynn in the 1994 strike-shortened season with a .394 batting average and after that, George Brett with a .390 batting average in 1980 (although he only played 117 games that season as opposed to Williams’ 149 in 1941). With today’s game evolving into a hit a home run or strike out mindset, Williams mark of .406 will most likely never be matched again and every year a new player will challenge the mark early, but none will ever be able to last an entire season hitting .400 again, making Williams’ mark all the more impressive.

Despite how incredible hitting .400 was, Williams favorite part of the 1941 season was not even his batting average, but it was, however, something he said later in his life “remains to this day the most thrilling hit of my life.” In the 1941 All-Star Game, Williams was batting fourth behind Joe Dimaggio and in the bottom of the ninth inning, with the American League losing 5-3, Ken Keltner and Joe Gordon singled, and Cecil Travis walked to load the bases.

Joe Dimaggio came up with a chance to win the game and hit a ground ball to the shortstop, Billy Herman, who got the out at second and then threw the ball away to score Keltner and give Ted Williams a chance to win the game with runners on first and third and the score 5-4 in the National League’s favor. Williams came up and crushed a home run to left field to give the American League the 7-5 victory. Williams rounded the bases jumping up, smiling and clapping as if he had just won everyone’s lunch money on a school ground bet. Williams would never forget that home run as long as he lived.

Ted Williams was drafted into World War 2 in January of 1942, but due to a legal issue regarding Williams being the sole supporter of his mother, Williams was able to play in the 1942 season. Williams had an incredible year to follow up his .406 season, hitting .356 batting average with 36 home runs and 137 runs batted in en route to winning the Triple Crown. Williams came in second in the MVP voting to New York Yankee Joe Gordon. Williams said that “the reason I didn’t get more consideration was because of the trouble I had with the draft boards.” After the 1942 season, Williams was on his way to war.

“Ted only batted .406 for the Red Sox.” said World War 2 fighter pilot, future astronaut, and Senator John Glenn, “He batted a thousand for the Marine Corps and the United States.”

Williams would serve as a fighter pilot for 3-years in World War 2 (Imagine Mike Trout or Aaron Judge doing that, just to put it into perspective) and like baseball, Ted excelled as a pilot, setting records in hits, shooting from wingovers, zooms and barrel rolls. Williams additionally set a still-standing student gunnery record, in reflexes, coordination and visual reaction time.

“Some people came back in from the sports world who were put to work as coaches for the baseball teams or something like that,” said John Glenn. “Ted was not that way. Ted fit right in. He was a Marine pilot just like the rest of us and did a great job.”

Williams missed 3-years of his prime while serving our country in the war and when he came back to the big leagues, it was like he never left, hitting .342 with 38 home runs and 123 runs batted in. Williams finally won the first Most Valuable Player Award of his career that year. It was clear the nothing was going to slow down the great Ted Williams, not even the war.

Williams led the Boston Red Sox to their only World Series appearance during his tenure in 1946 and after the Sox clinched, they had spare time in which they played practice games against an All-Star team so that the club would not get cold. Williams was hit with a curveball on his elbow by Wahington Senators’ pitcher Mickey Haefner. Williams would not be able to swing a bat for four days and when it came World Series time, Williams’ arm was incredibly sore. Williams went just 5-25 (a .200 average) with just one run batted in. When asked 50-years-later what one thing he would have done differently in his life, Williams replied, “I’d have done better in the ’46 World Series. God, I would”.

Williams would never play in another Fall Classic.

From the years 1947 to 1951, Williams continued to prove that he was the best hitter in baseball, winning his second career Triple Crown Award in 1947, his second career MVP Award in 1949, while also putting up a stunning .340 batting average up with 158 home runs and 623 runs batted in during those 5-years. Unfortunately for Williams, World War 2 would not be his only go around in the Marine Corps.

Ted Williams was called from a list of inactive reserves to serve on active duty in the Korean War on January 9, 1952. Williams was only able to play in 37 games in 1952, hitting .407 with 13 home runs and 34 runs batted in before passing his physical and being shipped off to Korea. Williams was livid that he was once again going to have to leave baseball for war, but he stayed calm and composed and left to an incredible ceremony held in his honor by the Red Sox called “Ted Williams Day”.

Williams would miss another two seasons to the Korean War, bringing his total of missed time due to military service to 5 years. Williams, who was once called a coward and a draft dodger after not going to war in 1942, became the only Major League Baseball player to ever serve in both World War 2 and the Korean War. Williams simply found a way to prove people wrong in every scenario possible.

“Everybody tries to make a hero out of me over the Korean thing,” Williams once said. “I was no hero. There were maybe 75 pilots in our two squadrons and 99 percent of them did a better job than I did. But I liked flying. It was the second-best thing that ever happened to me. If I hadn’t had baseball to come back to, I might have gone on as a Marine pilot.”

Williams returned to Major League Baseball after the Korean War and did not skip a beat with his hitting. Williams continued to dominate and prove to be one of the greatest hitters of all time. In the year 1957, the 38-year-old Ted Williams was supposed to be entering the declining stage of his career, instead, Williams continued to shock the world and hit an incredible .388, becoming the oldest player to ever win a batting title, a record that would stand until 1958 when a 39-year-old Williams hit .328, breaking his own record (one that has still not been broken).

“He studied hitting the way a broker studies the stock market,” said Carl Yastrzemski regarding the “Splendid Splinter” as Wiliams would famously be called.

Williams had a rough 1959 season in which he hit a subpar .254, the only time Williams ever hit below .300. Williams age was starting to show and legend has it that the season before Ted retired, he went in to discuss his options (and contract renewal) with Boston Red Sox General Manager Dick O’Connell. Williams had made up his mind that this next season would be his last and went into the negotiation knowing this.

“Here it is, Ted,” Dick O’Connell said. “Same as last year.” Meaning a salary of $125,000, the highest in baseball at the time.

But Ted said no, and that he “hadn’t deserved” what he made in the previous season, and that he would play one more for $90,000 – a $35,000 pay cut, or a loss of about 30 percent. O’Connell gladly accommodated Williams’ wish and Ted played that last season for exactly $90,000.

This story just goes to show the unique meticulousness that Williams invested in the craft of hitting. Williams never wanted to take something he didn’t earn and in his final season, Williams hit .319 with 29 home runs.

In Williams’ final career at-bat, Williams came up against Jack Fisher looking for a fastball and got one, he took a big hack at it and missed. “…I swung and I couldn’t believe I didn’t make contact,” and then said that “I was watching Fisher and he can’t wait to get the ball back from the catcher and I’m thinking ‘he thinks he threw it by me’ then he threw it in the same spot same speed…” and Williams crushed a high and deep fly ball out to left center field in his final career at-bat for career home run number 521.

Williams had always had issues with the Boston media (possibly costing him at least 3 Most Valuable Player Awards) and after hitting his final career home run, no matter how much the fans cheered, Williams couldn’t bring himself to tip his cap to the crowd. Williams had been wronged so badly by the Boston media, that in the perfect ending to the greatest hitter of all-time’s career, he could not bring himself to salute the fans. writer John Updike later justified the moment by stating, “Gods do not answer letters.”

Ted Williams retired with one of the greatest MLB careers of all-time under his belt. Williams ended his career with the highest on-base percentage in Major League history at .482. Williams once got on base in eighty-four straight games (in 1949), an incredible feat that remains unmatched to this day. Williams was a 19-time All-Star, a 2-time Triple Crown Award winner, a 2-time Most Valuable Player Award recipient (while finishing either second or third in the voting 5 times), a 6-time American League Batting Champion, and led the league in an offensive category 71 times in his career.

Ted Williams is one of just 29 players in MLB history to date to have appeared in Major League Baseball games in four different decades. Williams is also one of only four players to hit a home run in each of four different decades, the others being Willie McCovey (who, like Williams, also retired with 521 career home runs), Rickey Henderson and Omar Vizquel.

Williams finished his career with 521 home runs, 1839 runs batted in, a .344 batting average, a .634 slugging percentage, a 190 OPS+ (100 is league average) and a 1.116 OPS. Williams finished his career with 2021 walks as opposed to just 704 strikeouts. Williams had done what he had always dreamed about, become the greatest hitter to ever live.

A recap about Williams’ final career statistics would not be complete without mentioning what Williams’ numbers would have been like had he not fought as a United States Marine. In an article by Sports Illustrated that looks at what could have been if Joe Dimaggio and Ted Williams never went to war states the following:

“Baseball historian Dean Hybl took the average of Williams’s three seasons before and after military service. As it was, Williams finished with a .344 average, 2,654 hits, 521 home runs and 1,839 RBIs—no-brainer HOF numbers. But using Hybl’s formula, Williams would have batted .342 with 3,452 hits (instead of ranking 75th he would be seventh, behind Derek Jeter), 663 home runs (fifth, ahead of Willie Mays, instead of 20th) and 2,380 RBIs (first, ahead of Hank Aaron, instead of 14th).”

Personally, I think his numbers would have been even better.

Williams would retire from baseball and spend his years away from baseball as an avid fisherman. Williams was just as meticulous with the craft of fishing as with the science of hitting. Williams would keep a log of the fish he caught, on what lure, in what weather, etc. Williams was elected into the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame and the Saltwater Fishing Hall of Fame.

“Why fishing?” Williams said about the hobby. “All right. It’s the outdoors. The beautiful surroundings. The trees. The streams. The ocean. The fresh air.

“It’s the anticipation of the strike, the anticipation that with every cast something might happen. The love of making the perfect cast. The love of just being there, away from telephones, away from people.”

Williams would be elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966 on the first ballot with 93.4 percent of the votes. Williams opened his speech by poking fun at his poor relationship with the press, stating, “I received two hundred and eighty-odd votes from the writers,” he noted. “I know I didn’t have two hundred and eighty-odd friends among the writers. I know they voted for me because they felt in their minds and in their hearts that I rated it, and I want to say to them: Thank you, from the bottom of my heart.”

Ted Williams, being the kind of guy he was, also did not hesitate to advocate for African American baseball players during his Hall of Fame speech, paving the way for Negro League players getting inducted into Cooperstown.

“I hope that someday the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way could be added as a symbol of the great Negro players that are not here only because they were not given the chance,” Williams told the crowd.

At the time of his election, there were only 26 players in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. “I thought that day how great it would be to have a career that makes you worthy of the Hall of Fame, and how much I wanted it,” Williams said. “Just a boy and his dreams.”

There comes a point in a man’s life where he truly realizes how many people he affected over the course of his life, whether it is in a positive or a negative way. In my personal opinion, that moment came for Ted Williams when he made an appearance at Fenway Park prior to the 1999 All-Star Game.

Williams was driven out on the field from center in a golf cart while wearing a white hat with “Hitters.net” embroidered on the front as he waved his cap to the fans who were cheering wildly after an incredible introduction. It seemed as if Williams was making up for a lifetime of not tipping his cap during the ride to the pitcher’s mound where he was mobbed by the 1999 All-Stars.

Players such as Tony Gwynn, Mike Piazza, Ken Griffey Jr., Mark McGuire, Nomar Garciaparra, and Tony Gwynn all huddled around Williams with hopes of shaking his hand and saying something to the greatest hitter of all-time. As the fans cheered and Williams spoke with the players, the announcer actually had to come over the intercom and tell the players to return to their respective dugouts so the game could begin. Many players ignored this wish in order to continue speaking with Williams.

Williams threw out the ceremonial first pitch to Carlton Fisk with the help of Tony Gwynn and was bombarded with applause from the Boston Faithful that had grown up idolizing the Splendid Splinter.

“I thought the stadium was going down,’’ Red Sox All-Star and Hall of Fame pitcher Pedro Martinez said. “I don’t think that there will be any other man that’s going to replace that one.”

Ted Williams passed away on July 5th, 2002. The baseball world was struck with an immense amount of sadness at the loss of the sport’s greatest hitter. Williams death was a horrible time for baseball and while millions of fans mourned the loss of their hero, Williams’ head was being sent to a cryonics facility after his will was controversially altered stating that he would like to have a chance to reunite with his family (Williams was not a religious man) once again on earth.

Regardless of his final resting place, Ted Williams will never be forgotten. Some will remember him as a United States Marine, a Hall of Fame fisherman, or a generous supporter of the “Jimmy Fund,” but everyone who ever has or will hear or speak of the name Ted Williams, will know that Williams was a man who had a goal from the time he was very young, and made that dream a reality, so that whenever he would be walking along the streets, people would stop and say, “There goes Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived.”

One thought on “Doubleday Double Talk Remembers: Ted Williams”